The physical colonisation of Australia occurred in stages from 1788 to the last remote areas in the early 20th century. The framework for this colonisation however had been firmly established during the expansion of Britain’s colonial empire. In 1768, when captain James Cook and Sir Joseph Banks set out on the HMS Endeavour to seek evidence of ‘the unknown southern land’, the process had begun. At every stage colonisation involved occupying and ‘settling’ land. The legal definitions and framework imported by the colonisers laid out distinct guidelines for the act of taking such land; this was to be done in a number of preferably peaceable ways, but in the case of Australia, a great myth developed from the beginning: that the land was for all practical and legal purposes uninhabited. This great ambiguity at the heart of Australian history establishes the foundations for this story. As subjects of the crown, Aboriginal people were supposed to be extended equal protection under the law, as a result, they were expected to conform to a law they knew nothing of. The absurdity of this situation seemed to be lost on the vast majority of colonisers, who armed with notions of racial superiority and the backing of empire set about laying the foundations of what was to become Australia. The imported framework for ‘civilisation’ had a predetermined social hierarchy which was to be transplanted in the new lands, one which brought its own set of legal requirements and punishments. As it is to this day, when a law is broken, the first point of contact in resolution is the police. During the colonisation of Australia, police effectively filled two roles, enforcing the imported legal structures amongst the European population and facilitating the aggressive expansions of settlers by transplanting a new legal system of the pre-existing population. As such, it is imperative to understand the development of policing in Australia within the context of colonial expansion.

The West Australian police web site lists in its brief historical overview that the first notable episode in West Australian policing was in 1834, it simply says ‘mounted police and Pinjarra’ (www.police.wa.gov.au). The event which this refers to is what has come to be known as the Battle of Pinjarra or the Pinjarra Massacre. A growing Nyungar resistance to the expanding demands of settlers saw an armed party of mounted police and citizens led by Governor Stirling set out with a plan to end any further native resistance. The ensuing fight saw large numbers of Aboriginals killed with only minor injuries to police and settlers. This first ‘notable episode’ in west Australian policing history is followed by what is described as ‘trouble settling the north’ and ‘Kimberly uprising’ (www.police.wa.gov.au). These are in reference to native resistance to expanding pastoralism in the north of Western Australia and Jandamarra’s four year guerrilla war in the Kimberley. To understand the development of this kind of policing and why these events are so prevalent in all Australian colonial police forces, one must understand the duties police performed on the Australian frontiers.

Central to any colonial expansion is land. The growing demand from pastoralists and squatters for land put up a unique legal challenge for the colonies. Squatters who were taking up vast tracts of land extending out from the periphery of the colonies were doing so against the law of the time and on Aboriginal territorial land. The squatter’s occupation however was providing an economic backbone for the colonies and as a result colonial governments moved to legitimise their occupation with the introduction of pastoral leases. Cunneen notes that the pastoral leases which legally facilitated this land grab were an entirely new form of land tenure and with its establishment came a need for a new form of policing which manifested in the establishment of the border police (Cunneen 2001, 47). The Border Police were established to facilitate the squatters land grab while offering ‘protection’ to the Aboriginal people whose land was being taken. That they operated more as a private security for those ‘outside the boundaries of settlement’ is hardly surprising, this unique form of land tenure and policing must be understood within the specific context of the colonial setting. That the police were established as a reflection not only of the needs of the official colonial establishment but also the needs of ambitious squatters who were initially operating outside of colonial sanction is indicative of their intent. The police often functioned as a first line of contact between Europeans and Aboriginals and although they were in theory supposed to represent Indigenous people equally as subjects of the British crown, the representational relationship is fundamentally skewed towards serving the interest of settlers. By supporting the radical expansion of land holds and facilitating the way in which Indigenous people were engaged, the police in colonial Australia were performing a task which had in other colonial enterprises been carried out by the military (Cunneen 2001, 49). Rather than maintaining law and order police were “extending the reach of British jurisdiction over resisting Aboriginal communities” (Cunneen 2001, 50). That the police functioned as a political and military tool, utilised to facilitate not only the acquisition of land but the establishment and enforcement of a new system of law over existing Indigenous communities, is why it is essential to understand the development of policing in Australia within a colonial context.

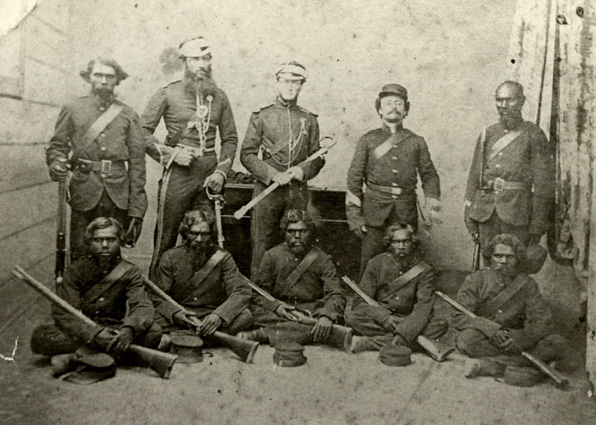

Punitive expeditions exemplify the attitudes of colonial police towards Aboriginal people. In fact the police in NSW effective took over the coordination of retaliatory action against Indigenous people from the military and gangs of squatters. Early in the NSW colony the threat of Indigenous resistance on the Hawkesbury was great enough to warrant the guarding of farms by the military (Connor 2010, 5). The tit for tat nature of conflict between settlers and Aborigines set the stage for a punitive model of policing. More often than not an attack on a squatter’s property or stock would warrant a severe police lead retribution. The development of the Native Police was central to colonial approaches to dealing with the perceived threat Aboriginal people posed. Possibly the most brutal police forces ever to exist in Australia, the Native Police were utilised in suppressing the independence of Indigenous groups and bringing them into the fold of colonial authority (Nettlebeck 2010, 361). Usually consisting of around ‘six to eight Aborigines led by a European officer’, they were equipped with a horse, gun and uniform (Richards 2008, 1025). The Native Police were used as a paramilitary unit which has seen them described as “the most lethal force ever used against Aboriginal people” (Cunneen2001, 56). Violence enacted against Aboriginal people by Native Police on behalf of the settlers was at the time seen by many as a necessity (Evans 1975, 28). The nature of colonial expansion and the political and scientific sentiment of the time was promoting amongst other things that the Aborigines were at the bottom of the social evolutionary scale, they had to conform to a broader European agenda or perish, as many believed they would. The effectiveness of the Native Police in quelling Aboriginal resistance is undoubtable. Competent in the bush and with a knowledge of country inaccessible to white colonists, the Native Police exacted a bloody regime on behalf of the colonial establishment. Queensland native police developed a particular reputation for brutality. The apprehension of suspects came secondary to use of lethal force, targeting not only suspects but everyone at camp (Cunneen 2001, 58). The sensibilities of the time and perhaps the hesitancy of officials and police to record much explicit evidence saw the term ‘dispersal’ come to represent the killing of Aboriginal people (Richards 2008, 1024). Dispersals became the primary tactic of the Queensland native police.

The native police served a political function in the colonies. The perceived threat posed to settlements and colonial authority from Aboriginal resistance required a mechanism of punishment and control. In this sense the Native Police were able to operate outside of the law. The ambiguous nature of Aboriginal rights under British law allowed many to turn a blind eye while the Native Police settled matters. Implicit in this arrangement was the knowledge that the native police were able to “take Aboriginal lives almost with impunity” (Slocomb 2011, 85). The members of the native police were usually sourced from areas outside of where they served, but the psychological element must have contributed to their fierce reputation.

Colonial policing adopted other models and ways not only of utilising Aboriginal people but more generally in enforcing rule of law in the settlements. Cunneen notes that centralized approaches to policing is representative of the levels of conflict between settlers and Aborigines. In the case of Tasmania, localised police constabularies existed until the end of the 19th century, Cunneen attributes this to the early conclusion of hostilities between Aborigines and settlers (Cunneen 2001, 48). The connection is important to note, the coordination of a military style police force to respond to Aboriginal threat would be much more effective from a centralised control. In the 1820s the threat posed from bush rangers and Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land saw Governor George Arthur establish the field police. Consisting primarily of veterans of the French Wars, the field police were established along the lines of militias organised into five administrative districts (Boyce 2008, 174). The district police magistrates answered directly to Arthur, this centralised approach highlights Cunneen’s point. While the threat remained, the police served primarily an oppressive function. Aborigines from the mainland were sent down to operate as guides and contribute to punitive missions (Harman 2009, 5). The peak of oppressive government action against Tasmanian Aborigines came in 1830 with the Black Line. The line consisted of two thousand soldiers and civilians and was intended to drive four of the nine Tasmanian tribes off their homelands, thus ending the black war (Ryan 2013, 3). While the black line was not successful in its stated intent, it served to consolidate the Tasmanian Aboriginals under the control of George Augustus Robinson. The effective combination of oppressive police and military action in Tasmania allowed the colonial police force in Tasmania to develop along a different trajectory after the conclusion of the Black Wars.

In Western Australia a different form of colonial policing developed. Aborigines were utilised as trackers and native assistants to the police, particularly in the Kimberleys. Police working closely with squatters served as an oppressive force against local Aboriginal groups (Cunneen 2001, 58). A greater emphasis was given in WA to the apprehension of Aborigines than was in Queensland but a great number of Aborigines were still killed by police. Rottnest Island was established as a jail for Aboriginal men caught for any number of misdemeanours and the terrible conditions on the island saw many die. Central to the police mission, as elsewhere in Australia, was to facilitate to acquisition of land. To impose a system of British law over the local Aboriginal populations while relinquishing them from their traditional lands was the police’s primary function in the Kimberleys. Central to their success was the use of Aborigines as trackers and assistants. Perhaps the best known police assistant was Jandamarra, a Bunuba man who after serving as a police assistant for years turned his gun on the police and led a war of resistance against police and squatters for four years (Shaw 1983, 9). Both of these events are referred to as the notable events on the West Australian police website mentioned earlier. As with other models of colonial policing in Australia, the ambiguity of the legal status of Aborigines was used as a justification to the brutal methods of policing that were developed.

What highlights the difference between colonial models of policing in Australia and more conservative understandings of police function is intent. The primary function of colonial police in Australia was a military one. The ambiguity stemming from Joseph Banks suggestion of Terra Nullius left Aboriginal people in a legal void. To consolidate the growing need for land in the colonies the police functioned as an oppressive force to acquire new territory and subjugate the traditional inhabitants to a new system of control. Throughout Australian history, police have been at the forefront of Aboriginal contact with the colonial system. From frontier wars and land grabs, to the stolen generations and the regulation of assimilation policies, police have been at the forefront. Often these relationships have centered around coercion and violence on behalf of the police. More recently we have seen the police and military utilised as the first line of action in the Howard governments federal intervention and as recently as the 1960s police have been central to industrial land grabs, such as the forceful eviction of residents of Mapoon in the Cape York Peninsula (Wharton 1996, 39). Police brutality and Aboriginal deaths in custody have led to riots in Redfern and Palm Island. These events in many ways are indicative of the past. Understanding police as a coercive force within the context of colonisation is an important tool in understanding police relationships to Aborigines in contemporary society. The police in many ways continue to be an extremely effective mechanism of control when it comes to relationships between Aboriginal people and the broader institutions and legal systems of Australian society.

Boyce, J. 2008, Van Diemen’s Land, Black Inc, Victoria.

Connor, J. 2010, ‘The Frontier War that Never Was’ in Stockings, C. (ed.) Zombie Myths of Australian Military History, UNSW Press, Sydney.

Cunneen, C. 2001, ‘The Nature of Colonial Policing’, Conflict, Politics and Crime: Aboriginal Communities and Police, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest.

‘ Episodes in our Policing History’, West Australian Police Website, http://www.police.wa.gov.au/ABOUTUS/OurHistory/EpisodesinOurHistory/tabid/1060/Default.aspx

Evans, R. Saunders, K. Cronin, K. 1975, Race Relations in Colonial Queensland, University of Queensland Press, Queensland.

Grassby, A. Hill, M. 1988, Six Australian Battlefields, Angus & Robertson, NSW.

Harman, K. 2009, ‘”Send in the Sydney Natives!” Deploying Mainlanders Against Tasmanian Aborigines.’, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, Vol. 14, pp. 5-24.

Nettlebeck, A. 2010, ‘Policing Indigenous Peoples on Two Colonial Frontiers: Australia’s Mouned Police and Canada’s North-West Mounted Police’, The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 356-75.

Richards, J. 2008, ‘The Native Police of Queensland’, History Compass, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 1024-36.

Ryan, L. 2013, ‘The Black Line in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), 1830’, Journal of Australian Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 3-18.

Shaw, B. 1983, ‘Heroism Against White Rule: The ‘Rebel’ Major’, in Fry, E. (ed.) Rebels and Radicals, Allen & Unwin, Sydney.

Slocomb, M. 2011, ‘The Harris Case: the Murder of an Aboriginal man by the Native Police in the Burnett District 1863’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 13, pp. 85-104.

Wharton, G. 1996, The Day They Burned Mapoon: A Study of the Closure of a Queensland Presbyterian Mission, BA Thesis, University of Queensland